Jeanne Dielman, 1080 Brüsszel, Kereskedő utca 23.

-

Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (több)

Tartalmak(1)

A film egy megözvegyült anya főzéssel, takarítással, gyerekneveléssel és ügyintézéssel töltött, szigorúan beosztott idejét követi három napon át. A nő (akinek a neve, Jeanne Dielman, csak a címből és egy felolvasott levélből derül ki) azzal biztosítja megélhetését, hogy minden délután más-más ügyfelet fogad a lakásán, mielőtt a fia hazaér az iskolából. Jeanne számára a szexmunka is a hétköznapi rutin része. A második napon, az aktuális ügyfél látogatása után Jeanne fegyelmezett viselkedése megváltozik. Vacsorakészítés közben túlfőzi a krumplit, majd a fazékkal kezében céltalanul bolyong a lakásban. Elfelejti rátenni a fedelet a porcelánedényre, amelyben a pénzét tartja, távozás után felkapcsolva hagyja a villanyt a szobában, kihagyja az egyik gombot a köntösén, és elejti a frissen elmosott kanalat. Ezek a furcsa változások egészen addig folytatódnak, amíg a harmadik napon meg nem érkezik az aznapi ügyfele. Az aktus után Jeanne felöltözik, egy ollóval leszúrja a férfit, majd csendben leül az ebédlőasztalhoz. (CirkoFilm)

(több)Recenziók (5)

Főzéstanfolyamok, étkezés és kávéfőzés a bűnös Jeanne asszonnyal. Formai minimalizmus, kisebb eltérésekkel az ismétlődő tartalomban. Néhány nap lefolyásának procedurális megfigyelése egy hölgynél, aki reggel elkíséri a fiát a munkahelyére, este pedig együtt vacsoráznak és néhány szót váltanak. Közben főz, elmegy bevásárolni, fizetség ellenében férfi látogatót fogad, zuhanyozik, vacsorát készít... Bepillantás a magánéletbe, amely annyira szó szerinti és színészileg koncentrált, hogy voyeurisztikusan jobban kielégít, mintha dokumentumfilm lenne. Akadémikus tisztaság, amely az egyetlen szereplővel, intim körülmények között eltöltött idő miatt megmarad a fejedben.

()

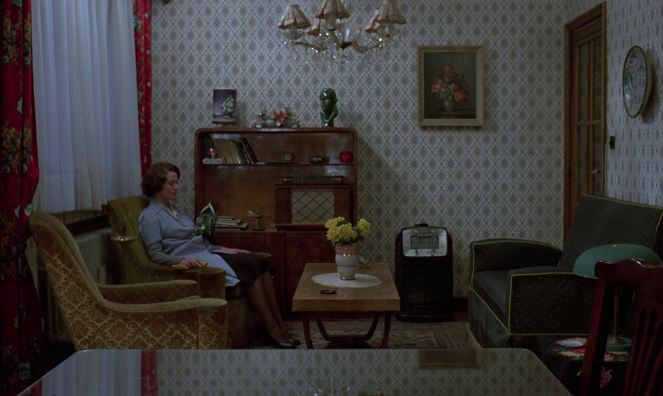

Every neorealist’s dream come true. Even though there is always something happening in this film (cooking, cleaning, setting the table, knitting), it lacks a dramatic plot in the usual sense of the word. It is neither action- nor goal-oriented, nor does it contain any external conflicts. It is more or less composed of scenes “between events”, which would have been cut from a standard narrative film. With hypnotic cyclicality, the same actions are repeated again and again. The concept of space and time is also subordinated to them. The shots are mostly as long as the duration of Jeanne’s activities. She sets the film’s rhythm. The enclosed space-time of the household is an extension of her personality, which, unlike the male protagonists, she does not try to overcome and destroy, but conversely embraces with masochistic humility. Though the interchangeability of the individual days reinforces our conviction that nothing will ultimately happen, when we grasp Jeanne Dielman from the opposite end, we can watch it a second time as a film in which pressure builds up for three hours and will have to be released in some way. It is necessary to understand the radical final gesture from the perspective of the second wave of feminism, which perceives the body as a weapon, identifying the personal with the political. In other words, we shouldn’t consider Jeanne’s action as mere evidence that she has been pulled out of the cyclically repetitive housework. The minimalistic style of frontally shot, symmetrically composed, long and static shots, empty monologues (which primarily have a rhythmic function, as they do not communicate much through their content) and mise-en-scène, in which the slightest change plays a role, does not serve to tell a story with spiritual reach, unlike the films of Bresson and Dreyer. Spiritual reach is exactly what is missing in Jeanne Dielman’s life. While she finds the daily routine stultifying, the film takes on a hypnotic quality thanks to its unchanging rhythm and shot compositions, whose balance reflects Jeanne’s obsessive need for order. We gradually begin to notice the colours, the lighting, the interplay of horizontal and vertical lines and the placement of objects in the shots. Every movement and every change of angle takes on meaning. The director thus does not have to draw our attention to changes through editing or dramatic music. Every disturbance of order becomes exciting in a space with similarly rigid rules and the most gripping scene in the film may be the one in which we wait to see whether the milk bottle whose stability has been disrupted will tip over and spill. Similarly fragile stability and the need to disrupt it are thematised on another level throughout the film, which is worth as much as several feminist essays. 90%

()

I don't know what else to call it, so I'll call it "tyranny of the camera." While in conventional films, the camera constantly cowardly submits to the movement of the actors, this truly authoritarian camera finds its (static) place and then we only observe how the characters must submit to the space that had been defined for them by its framing (and the fact that this camera is truly uncompromising is beautifully evident in the occasionally decapitated heads of disobedient characters...). Traditional camera and editing surrender to the story's pleasing and seemingly natural narration, in which time ellipses serve to unrealistically cut out seemingly unimportant scenes. Akerman allows the camera to capture even the "boring" parts, and in that, she discovers more than all "Hollywood" stories combined (Akerman, unlike Truffaut, would not omit a traffic jam...). In this case, it penetrates deep into the stereotype of the lifestyle (see feminism), in which even the smallest deviation from the norm can become an explosion of suppressed frustration.

()

Jeanne Dielman is a cinematic paradox in that it forces the audience to look at what they usually run away from in films. The stiff compositions emphasise ordinary, everyday life in all of its horrible uninterestingness and soul-crushing triviality. The titular Jeanne, into whose inner self we don’t have even the slightest insight, shows how all of our actions, when free from our inner voices and thoughts, outwardly appear to be only the drudgery of mindless routine. Chantal Akerman shows the invisible and overlooked actions that are bound to the maxim of making sure that everything is as it should be – according to others and for others, of course. Potatoes don't peel themselves, the dishes don’t wash themselves, the bed doesn’t fold out of the couch already made, shoes don’t shine themselves in the morning and that lost button doesn’t just reappear on a coat. The somnambulistic narrative stimulates the desire to rebel, to break free from the dictates of roles imposed based on gender. But life goes on and is just as merciless and hopeless with each passing second. I would like to say that we have come a long way, that housework and cooking are a shared field outside of the obsolete gender dictates, and that we are even able to enjoy it – after all, it can be a lifestyle and the basis of a stellar career. However, this cinematic excursion into the flipside of that ideal can show us that, at the absolute core, the only thing that has changed in the past fifty years is how caretaking has been subjugated and transformed by capitalism for its own purposes, or how we have less space to think about our daily routine. The frightening nature of the world presented in the film is derived primarily from the total absence of distractions and from resigned apathy. But is it really so different from our present, which is more sophisticated only in the way constant distractions help us to not see the depressing insignificance of our existence and adopted roles? It’s no coincidence that advertisements tell us, “When your life flashes before your eyes, make sure it’s worth watching.” Conversely, Chantal Akerman allows us to watch 202 minutes of seemingly nothing. Thanks, however, to her record of ordinary housework, we get a chance to break free from the hasty effort to soak in new perceptions, to play multiple appropriated roles and to fulfil ourselves through consumption. We may even find ourselves surprised that we actually envy Mrs. Dielman for her moments of apathetic boredom. While she waits until she is able to fulfil her adopted role with the ringing of the doorbell or the sound of keys in a lock, we merely scatter our thoughts in the smog of media and social networks. Despite cynical and overly clever expectations during the three days condensed into the film’s three hours, Ms. Dielman fulfils one of the essential aspects of feminism. Prompted by both seen and merely intuited circumstances (among other things, Akerman pointedly formulates the horror dimension of the screaming infant and expands the pantheon of merciless movie villains with the addition of the grandmother who has taken the protagonist’s usual place in the café), she steps out of her shell of accepted passivity and takes action. But catharsis and liberation remain only a momentary distraction. The next day, there will still be cars passing by the windows and those porkchops aren’t going to fry themselves. So, let’s stave off the gloom with some gossip and get back to the machines, or as they say on FilmBooster: 87% and an extra star for the towel.

()

(kevesebbet)

(több)

Even though I wanted to hate this movie because it is unbelievably long, I have to admit that it has its qualities. It makes you think. Like, why does it do all of this, why doesn't it talk, why doesn't it sing, why doesn't it listen to something while doing housework. All of this and much more justifies what it eventually does. Definitely an interesting and not nonsensical approach to the movie.

()

Hirdetés