Rendező:

Zdenek SirovýOperatőr:

Jiří MacháněZeneszerző:

Jiří KalachSzereplők:

Jaroslava Tichá, Ľudovít Króner, Josef Somr, Jana Vychodilová, Lída Roubíková, Jan Kühmund, Gustav Opočenský, Božena Böhmová, Josef Bartůněk (több)Tartalmak(1)

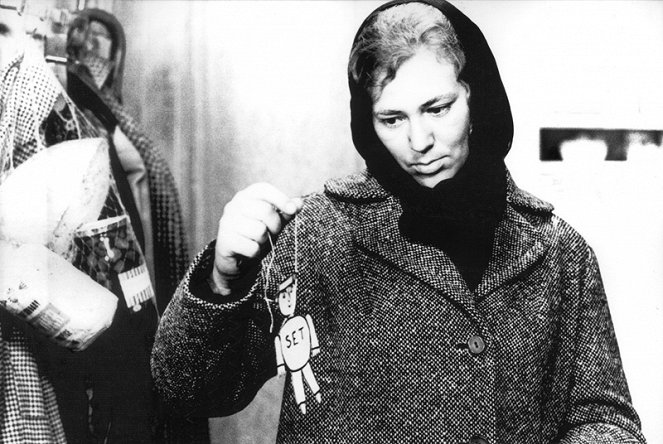

In 1965, the funeral of a farmer expropriated and evicted from his native village in 1951 becomes a public expression of the disapproval of the violent practices of the Communist regime. This dark ballad that ended up “in the safe” shows the perpetrators of injustice refusing to admit the guilt for ruining the lives of the others. (Summer Film School)

(több)Videók (1)

Recenziók (2)

A strong, open, disillusioning work, just like the literary years of the 1960s. I do not read Kantůrková's book, but Funeral Ceremonies corresponds relatively well to another (and unjustly neglected) prose from the sixties – the book Holy Night by Jan Procházka. In it we also find the motif of collectivizing guilt, the motif of the disintegration of the old order, and the motif of an irreparable catastrophe for which there is no catharsis. In Sirový’s story, a seemingly surprisingly large portion of the tragedy is concentrated in a negative character, but Somra's Devera fits into the tradition of disillusively portrayed characters of officials (in Procházka’s book, the power hungry peasant Picin has a similarly tragic fate). Funeral Ceremonies is not only a story of the failure of communism as an ideology that wanted to reshape a village - it is also a picture of the scarring of the village itself as a traditional order. The final funeral procession of the villagers is a kind of futile gesture, an attempt to redeem a moral failure in the time of collectivization, when many individuals succumbed to greed. Their reliance on the tradition of the funeral procession as a manifestation of unity with the unjustly destroyed farmer Chladil is thoroughly imbued with falsehood. Paradoxically, the real sufferers are Devera (whom his party colleagues throw amongst the people while they stand in the safety of the tower and watch everything), his wife Tonka (who is unable to overcome her feelings of guilt), and finally, Chladil's wife Matylda. Her tears, cynically framed by carnival merriment, are the only real sign of catharsis, which, however, does not bring relief, but only removes from the seemingly strong character her mask of untouchability (as well as her crying in a ruined orchard). Like Procházka, Sirový paints a picture of the village at point zero, when communism failed, humble faith in God disappeared, and only the carousel of guilt and the automatism of tradition remained. It was not the theft of land and property that caused the worst scars on the face of the village - it was the inalienable moral destruction for which there is no absolution. And so, as in Procházka's Holy Night, only one power remains valid and unshakable – nature and the traditions arising therefrom (the carnival, humility in death). A truly unhappy image, which must be interpreted more broadly in Sirový's film, towards the overall social horizon. At least that's how I "read" Funeral Ceremonies... definitely not only as a moral condemnation of communism, but as a deeper look, under the simple scheme of crime / criminal and punishment.

()

A man who obstructed so much even when he was alive is so malicious that he continues to obstruct even after death. The stubborn widow's decision to bury her husband as a victim of collectivization in their native village is a test for the regime, to see if it has learned to treat its presumed and actual opponents more humanely since the times of harsh Stalinism, to see if it has understood that it is better to persuade and set an example rather than to command and punish. It is a bitter and unpleasant intimate story, yet also a film that I consider to be one of the most significant artistic testimonies about the 1950s in Czechoslovakia. It is one of the gems of Czech cinema of the late 1960s and at the same time a film that was one of the first to be placed in the vault. Overall impression: 95%.

()

Hirdetés