Rendező:

Luis BuñuelOperatőr:

Edmond RichardSzereplők:

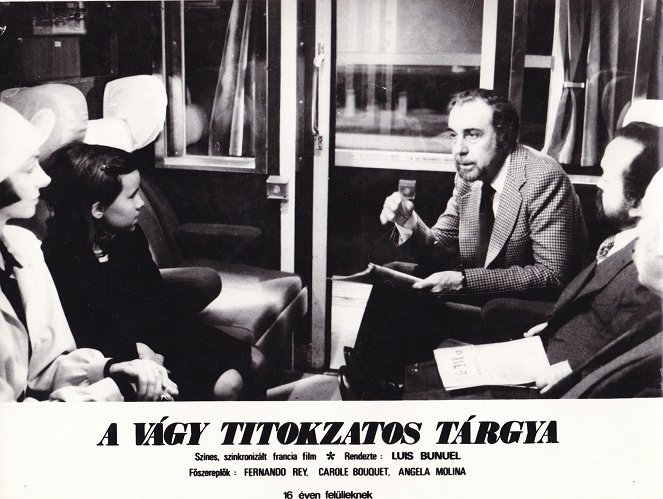

Fernando Rey, Carole Bouquet, Ángela Molina, Milena Vukotic, Julien Bertheau, Jacques Debary, Mario David, Bernard Musson, Piéral, André Weber (több)Tartalmak(1)

A jómódú, középkorú Mathieu beleszeret spanyol szobalányába, aki mindössze 18 éves. A férfi mindent megadna a lánynak, de az csak hitegeti a vágyba szinte már beleőrülő Mathieu-t... A nagy szürrealista rendező utolsó filmjében sem marad hűtlen önmagához: a spanyol szobalányt két, egymásra egy csöppet sem hasonlító színésznő játssza. (Mokép)

(több)Recenziók (3)

The unequal sexual and emotional relationship between an aging man and a significantly younger partner is one of the most common motifs that appear in artistic reflections of human relationships. Buñuel looks at his desire-obsessed foolish man with understanding (after all, he was 77 years old at the time of filming and was older than his protagonist), but at the same time, as is typical in his work, with an undisguised ironic detachment. One manipulative and temperamental hysteric with a hypocritical mother can really set the fire under Don Juan in his later years. Buñuel also mocks traditional bourgeois values and relationship rules that have survived out of inertia from long past times. He used his favorite actor Fernando Rey and the charms of the young Carole Bouquet, creating an entertaining game about the fact that not everything is attainable and not everything is worth striving for. Overall impression: 90%.

()

“Do you like sweets?” Even in Buñuel’s last film, the bourgeoisie still has a target on its back. This time, a man whose main concerns are food, sex and the fear of losing face is deservedly dragged from one situation that takes him out of the concept to another. Mathieu prides himself on his absolute control over his surroundings. He remodels the apartments in which his flings are to take place according to his own ideas in the same way that a director transforms a theatre stage. Control over the prepared performance gives him a feeling of superiority, the loss of which (i.e. deviation from the script) is severely punished. Any other disturbance of the order or the space of which he considers himself to be the master must be immediately eliminated (the absurd scenes with a dead rat and a fly in a drink). Every object belongs in a firmly specified place according to the protagonist’s opinion. It is thus no wonder that he attempts to integrate Conchita into the other interior furnishings. For Mathieu, she is not a sentient being, but merely a means of sexual gratification, a fetish. However – as it happens in Buñuel’s social satires – she is aware of this and is able to deal with it. Thanks to the degree of independence that the female character exhibits, That Obscure Object of Desire comes across as a delayed reaction to women’s liberation. The increased interest in social events, previously reflected by Buñuel on a more subliminal level, is also revealed by the violent inclusion of terrorist acts in the narrative. It seems that the lifelong surrealist shortsightedly embraced this new form of anarchism as an effective defence against the rottenness of the bourgeoisie. As with the film’s other motifs, Buñuel fortunately uses exaggeration in working with this one. Such exaggeration is present in That Obscure Object of Desire both at the level of individual scenes and in the overall narrative structure (the initial situation is reminiscent of an anecdote in the style of “A bourgeois, a dwarf and a respectable lady meet in a train compartment...”). In comparison with his previous films, it is more difficult to tell when this was still a matter of the director’s subversiveness and when it was simply a lack of creativity and ideas. For example, the sound – with the exception of the gag at the very end – is very shoddy (which, however, is entirely understandable in light of Buñuel’s deafness), too many scenes are stylistically indistinct and blend together, and the story is essentially just a variation of The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. In that film, members of the bourgeoisie are unable to sit down to dinner together, while in That Obscure Object, Mathieu cannot lie in bed with his chosen girl. Despite its richness of thought, That Obscure Object of Desire is mainly just an echo of the better works by a filmmaker from whom others (Saura, Almodóvar) had already taken over the surrealist baton by the time it was released. 70%

()

An Oscar for the screenplay? It is in fact a mere mockery of Pierre Louÿs and all the other versions, which are only here again by accident and mechanically transferred into Buñuel's self-centered conception. It is surely no coincidence that this great poseur ended his work by dwelling on the whims of the provocateur Conchita, but let us let you continue to dream your naive dream of Louÿs' originality. I'm off to check out the Bardot version and remain contentedly wringing my hands over the delights of von Sternberg and his fixated on the divine Marlene.

()

Galéria (32)

Photo © Mokép

Hirdetés