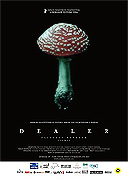

Rendező:

Benedek FliegaufForgatókönyvíró:

Benedek FliegaufSzereplők:

Felícián Keresztes, Barbara Thurzó, Lajos Szakács, Anikó Szigeti, Edina Balogh, Emmanuel Bonami, Dusán Vitanovics, Katalin Mészáros, István Lénárt (több)Tartalmak(1)

A dealer két éve jött le a heroinról, azóta szenvtelenül, üzleti szakszerűséggel házhoz hordja biciklijén megrendelésre az anyagot. Hajnalban az elvonási tünetek miatt óriásivá puffadt Újvári atyához, a nemzetközi hírű szekta vezetőjéhez hívják. Második útja kórházba vezet: egy régi baráthoz, a heroinról szintén leszokott szépségfarm-tulajdonoshoz, aki idegességét oldandó befeküdt altatóval az új szoláriumba, amitől teljes bőrfelülete megégett, a veséje leállt. Most aranylövést kér, cserébe felkínálja a fitness-szalont. Ezután a dealer Vandához, volt barátnőjéhez megy. A valószínűleg tőle fogant hatéves Bogit a gyámügy el akarja venni Vandától, ha nem áll le a drogról, de a nő képtelen erre. A dealer magával viszi a kislányt, s alkalmi barátnőjére, Barbarára bízza. Barbarát külföldi partnere Lisszabonba hívja, de a lány vonzódik a dealerhez, s most már Bogihoz is. A férfi aznapi stációi: a kokós Dragan üzlettulajdonos famíliájának monoton siralmai, az egykori kosárlabda-tehetség teljes leépülésének látványa, majd a fiatal apa - két kisfia néma asszisztenciája melletti -, kisebbrendűségi komplexustól fűtött ásás-őrülete, végül a gomba-flash-ről lejönni képtelen matematikus-zseni napok óta aput-anyut hívó, véget nem érő vakogása. A nap folyamán a dealer szembesül két éve nem látott apjának, anyja halálos balesete (vagy öngyilkossága?) óta tartó mániás depressziójával. Bizonyossá válik, hogy Bogi a megváltást jelentheti, ám a kislány kérdése, hogy ti. együtt árulnák-e majd a "cuccot", felfedi a dealer megpecsételt sorsát. Bogi az anyja mellett marad. Mielőtt Barbara elutazna Lisszabonba, a dealer rábízza a kislányt. A nagy éjszakai parti után hajnalban, a fitness-szalonban beadja magának az aranylövést, majd befekszik a szoláriumba. (Mokép)

(több)Recenziók (1)

The perfect antithesis of Requiem for a Dream. Instead of a rhythmic automaton of physical symptoms, Fliegauf sees the drug as an automaton of nothingness, emptied existence. Victims of drug addiction are transformed into zero points of humanity by the subtle movement of the camera, marginally kept out of the direct perspective of the testimony and revealed as if through their own absence - what Fliegauf demonstrates is not the self-purposeful formal brilliance, but rather the castration that the drug performs (and yet one of the characters of the protagonist, a cured drug addict, asks: "The heroin is gone. But what's left of you?"). The junkies around whom the camera slowly circles are empty boxes, puppets, zombies, beings that (as Slavoj Žižek would surely add) can no longer be the subject of tragedy or comedy. Dealer is extremely fascinating precisely thanks to its program passivity - there is not a single shot that provokes or shocks. What provokes and shocks is surgical lack of participation, an empty space where we expect tragic engagement or a gesture of compassion. Iconic is the scene where the hero stands with his father over a depression in concrete, where his mother's body landed, trying in vain to convince his father that his mother is no longer there. The whole film works on the basis of empty spaces, cracks, the possible filling of which is a drug. Hence the long and certainly metaphorical picture at the end, in which we follow either a kind of travesty of birth or a psychoanalytic rift, an inexplicable trauma from which there is no escape in rationality. Dealer is a brilliant perspective of the safety of schemes which keep a person at a self-preserving distance from addicts as a radical otherness. I think Fliegauf's film quite uniquely touches on a much deeper essence than most films on the subject of drug addiction (in fact, all that I've seen so far). The film may be temporal in its focus, but deeply "Tarr-like" philosophical with its bleak and silent penetration of taboos.

()