Recenziók (536)

Poto and Cabengo (1980)

In his first American film, Gorin does not hide that he is a European intellectual and apprentice of Godard during the Maoist period. It is not that the movie is political-philosophical experimental agitprop, but because it explores fundamental questions of language and identity (the golden age of the linguistic turn in social sciences), social exclusion (the story of the daughters from a poor, half-immigrant family on the outskirts of San Diego's agglomeration is truly not just about cognitive psychology and linguistics...), and presents it all to the viewer in the sophisticated and playful form of a highly personal documentary - Gorin, just like during the times of the Dziga Vertov group, breaks the (pseudo)documentary norm of a separate object and narrator, enters the plot, comments on it, etc. Yet that alone would not be all that exceptional, but from the period less than ten years ago, Gorin also retained a feeling for the multi-layered construction of a narrative combining different media (the initial sequences combining Gorin's reflections and the initial introduction of the central theme with children's immigrant comics seem as if they came directly from the turn of the 1960s and 1970s) and especially the excellent separation of the visual and sound components, which is crucial for Gorin's meticulous tracing of the speech of both girls. It turns out that the discontinuous and disjointed composition of sound and image can also serve in the documentary field. /// However, Gorin did not overlook the socio-critical dimension, even though it is hidden under the guise of a peculiar nostalgia - the disappearance of a unique relationship and a unique language, accompanied by the adoption of the dominant language, doubles the fate of the entire family, which is sinking deeper and deeper on the social ladder as it adopts a foreign dominant language of social conduct...

Poznavaja bělyj svět (1979)

The main heroine between two men, Kira Muratova between two film worlds, and the Soviet Union between a muddy yesterday and a neat tomorrow. It is true that we can understand the script as Brezhnev idealization, but from the film itself, there is also a sense of resistance against any materialism in human relationships. Not only with typically Russian lyricism that I ever believed (and not condemned as kitsch) perhaps only in old Russian films. But it is mainly because of the central motto, the declaration of Ljuba, in which, among other things, says: "The most important thing in the world is true happiness. They don't produce it in factories, not even in the best ones." It is an antithesis of materialism and proof that the causality of the film does not meet the official communist ideology: in that transition - from the mud/bad relationship with Nikolay to the brand-new housing estate/great relationship with Mikhail - the soft piano literally screams to the viewer that Muratova sees this transition as caused by love itself, and not as something embedded in the concrete of material conditions. Mikhail is thus not a hero of socialist realism and historical materialism, but a lyrical hero who fell from somewhere from a different history (from a time when we did not fly into space but instead burned handmade ceramics). Love and happiness change us and our relationship to the world, not the other way around; there is no dialectic of both moments in the film, only a temporal synchrony of two internally unrelated motifs: the birth of love and the construction of a housing estate. That's why I give it one star less. /// Muratova, on the other hand, stands between two worlds - the film lyricism is balanced by her favorite formalistic games, here repetition, playing with the axis, and the camera.

Pravda (1969)

Indeed, this film has a clear ideological structure. Why? Because its authors (the Dziga Vertov Group) held these positions. How is it that they appear so outrageously in the film itself?! Because there is nothing like an "objective" "documentary" when it comes to social issues, and definitely not in the field of a POLITICAL documentary. Let us therefore leave the mentally lagging garbagemen to their waste (and their sweet dream that their ideological standpoint is objective...) and let us enjoy the originality, humor, and freshness with which Godard tried to create a new concept of revolutionary cinema - just as he tried to reveal both sides of the contradiction of social unity in the real world, so he tried to discover their new dialectical unity in the unity of art. To combine two contradictions - image and sound - into a new unity of opposites, a revolutionary film.

Premier (1977)

Cassavetes works excellently with the audience. Thanks to the intertwining of the main character's real life with the role she is portraying, which is mentally destroying her and against which she is trying to defend herself, we are constantly kept in suspense through real theater performances, rehearsals, and glimpses into the personal life of the aging actress. We, in my case, try to recognize who is actually speaking to us (I was holding my breath) during this tension. Is it the real woman-actress, trying to cope with the character she is playing and thus also dealing with herself? Or are these just prescribed words from her part (which, by the way, the author of the play - also an aging woman - could be speaking)? Is it an instant improvisation or rehearsed words? Although the ending is not as catastrophic as the previous almost two and a half hours, Cassavetes as a director and actor and Gena Rowlands deserve the utmost.

Privilege (1967)

The introductory spectacle: the police on stage beating people in order to protect them in reality, but whom?; a simulated revolt and virtual emancipation accepted as a gift from the outstretched hands of the consumer idol. The same gesture serves the same function, whether as a (marketing) symbol of rebellion calling for participation, or as a sign of mourning and return to humility/conformity = Watkins shows that the essence and meaning lie not so much in the content as in the form that people allow themselves to be led by (existentialism and the Moscow theater as a form for advertising walking apples; a rock & roll band playing for teenagers and the Lord himself; the relationship between the stage and the audience, the idol and the spectator, serves both fascism and late capitalism, etc.) /// Although the film was made based on someone else's work, Watkins, of course, couldn’t deny his alienating documentary style: even though the film is at its core a "normal" fiction, Watkins' genius is demonstrated in the perfectly alienating voice-over in the cathartic scene - at the moment when ordinary (consumer) films would celebrate the regained subjectivity and nature of the main character, Watkins ironically and coldly overlays it with external impersonal statements, thus relativizing her effort to break free from the clutches of the public from which she has become estranged. /// A critique of the film: Was it necessary to be so explicit and didactic at times?

Prospero könyvei (1991)

“Renaissance collections aimed to show the connection between natural and artistic forms, the transitions between the wonders of nature and human creations. The Kunstkomora thus presented a vivid image of the world in its multiplicity and breadth, according to natural philosophy and magic principles, that "everything is contained in everything" (omnia ubique). (Description in Umprum) Greenaway's films are this kunstkomora, in which the microcosm of the author's artistic vision burdened by so many internal images through a dark room is projected into the macrocosm of baroque overflowing mise-en-scène, a kunstkomora that wants to say everything and indeed says everything: one film image is not enough, the superposition of images duplicates the leafing through of a book, which is the definitive inventory of all knowledge - in Greenaway's work, films need to be seen as a natural transition from book to film and vice versa, as writing and knowledge can be aestheticized at any moment and visuality can always be absorbed by the alchemy of words which "was at the beginning" of everything and from which the author's mannerism also arose, in which the sole essence of the divine demiurge - the director - manifests not only through the seven liberal arts but through all artistic forms within the reach of classical spirit.

Provedu! Přijímač (2017) (sorozat)

Since I experienced Vyškov almost at the same time, albeit in a shortened form of a one-and-a-half-month basic training course for Active Reserves, instead of three months for future Voluntary Military Training, although 85% of the course content was the same, I can confirm that the documentary is, within its limits, very faithful. A time machine transported me a few years back and also to the 70s when the main part of the Vyškov complex was built. Of course, the film could have been more artistic, more critical, more contemplative, and it would have suited it better to be a sincere raw cinema vérité.

Rani radovi (1969)

Esthetic philosopher Boris Groys knew that the utopianism of communism lay in the attempt to replace the power of capital with the power of politics, which is nothing more than words - all power of discourse. This film is precisely the best dream of the performative power of speech: slogans are not templates, but a medium that brings events to life on the screen - it truly requires the viewer's attention to the moments when the characters' speeches generate a new, disjointed narrative sequence, symbolically connecting the jumpy editing with the inevitably unnatural/violent leap from immaterial word to material action. The true meaning of Mao's "Great Leap Forward" lies precisely here, and the Yugoslav hippie communists of the fourth way - the path between capitalism, Soviet state socialism, and Chinese Maoism of cultural revolution - try to find the mythical origin of phrases here, their real embodiment in existing political regimes has (?) profaned them forever. How else than to once again transform phrases into actions - but differently, newly, disjointedly: both in relation to previous attempts and to previous film art. Why couldn't Godard's Week-End become the basis for a new kind of film, just as Lenin's turn of the helm became the basis for a new concept of societies: that capitalism ultimately triumphed and suffocated the bad alongside the good that emerged in the field of real socialism and cinema Marxism, is nothing but a sad legacy of the present, which will make this film incomprehensible to many contemporary viewers. And this is characteristically true for a film that is so ironically critical of the former real socialism (albeit constructively!) that many anti-communists would envy: another example of how the baby is thrown out with the bathwater...

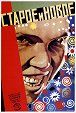

Régi és új (1929)

To be able to capture things beautifully, originally, and suggestively is an art, but discovering new, previously unsuspected, or unnoticed relationships among things is mastery. Eisenstein was able not only to capture the motionless beauty of things, nature, and masculine faces (otherwise terrifying...), but he was also able to capture the relationships between them. It is in the relationship between two or more things that tension and movement arise, which he was able to not only breathe life into but also capture with his dexterity. That is why there are both beautiful details and the dynamism of scenes in such situations, which would bore a different filmmaker capturing the construction of an agricultural cooperative in two silent hours. The analogy with humor and seriousness, the ability to create a visually breathtaking experience from the most ordinary scenes of haymaking or the operation of a milk centrifuge, is simply mastery, in my opinion. There is no choice but to agree with another master of the silent era, Griffith: "What the modern movie lacks is beauty – the beauty of moving wind in the trees, the little movement in a beautiful blowing on the blossoms in the trees. That they have forgotten entirely. In my arrogant belief, we have lost beauty." Considering the historical context of the film in the context of Russian history and the betrayal of the author's commitment to Stalinism, it is a tragic beauty.

Reifezeit (1976) (Tévéfilm)

A Film excerpt from the life of nine-year-old Michael, who spends his childhood between school and home, where only his mother - a local prostitute - waits for him. The formal aspects of the film correspond to the monotonous life of the boy - long shots, minimization of time ellipses, slow pace, and repetitive shooting and arrangement of shots in the same recurring situations. We are confronted with the gloomy adolescence of a child, who nevertheless lives or tries to live a normal life of children's games and dreams. Personally, this film reminded me of a one-year older film Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles by Akerman, in which there is an identical distribution of characters and their roles (although the director's focus on one of them differs) and, above all, a similar (although much more pronounced in Akerman’s film) formal process. Saless' film is very subtle and unspectacular, with meanings being casually presented - for example, the role of money in the lives of West German children, prostitutes, traders, and pensioners.