Recenziók (935)

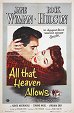

Amit megenged az ég (1955)

On the surface, All That Heaven Allows is schmaltz coloured like a Disney movie (with probably unintentional references to Bambi and The Old Mill), but beneath the surface it is a dark story about a woman whose emotional liberation is hindered by the primness of middle-class society. It is an altogether extremely rich experience, both emotionally and intellectually. A house in the suburbs, presented by the TV series and commercials of the time as a wonderfully idyllic place, is for the protagonist a hell from which she cannot escape. The way that television (de)formed and still deforms the social position of women is shown by the film’s probably most famous scene, when the protagonist’s reflection becomes a prisoner of the television screen that her son brought to her in the belief that his mother will no longer obstruct him on his path to success with her unseemly ideas. Her position is also reflected by other props, serving here as symbols of the conformist and consumerist life of people who close their eyes (or doors, as in the scene with the maid in the background) to social reality. Objects express what Cary, bound by convention, cannot say. Sirk conveys what is essential through those objects and through colours, lighting and camera angles, thus confirming his position as the most astute cinematic psychoanalyst of post-war American society. 85%

Felhőatlasz (2012)

Cloud Atlas is definitely a stimulating film, but I’m not sure what the directors’ primary intention was. I most enjoyed seeing how the all-encompassing favouritism towards minorities is related to the conventions of individual genres. Melodrama from the artistic environment was ascribed to homosexual romance, the main protagonists of an originally white paranoid thriller are a black female reporter and her partner, who were seemingly pulled out of a blaxploitation action flick. None of the genres employed in the film is entirely “pure” – the comedy is permeated with an escape movie, the thriller makes room for black humour – as the filmmakers acknowledge their own post-modern framing of the book on which the film is based, i.e. a point of view that doesn’t belong to any of the characters. Cloud Atlas is fine in its analysis of post-modern genre deconstructions, but it fails on a more basic level. I found the flat characters to be uninteresting. Contemplating who was hidden behind the mask was more entertaining to me than the acting. The six worlds are equally artificial, intended only for conveying certain transpersonal ideas. They are worlds for the camera, without a life of their own. So that we don’t doubt that one of the levels plays out in the 1970s, almost every exterior shot includes a car typical of the era (e.g. a Ford Mustang). The film fails to grip the viewer or offer a concentrated emotional experience. Taken together, the actions set in different time-space continua do not form a powerful sequence; on the contrary, they get in each other’s way and make it impossible for individual scenes to resonate. If the intention was to make it difficult for viewers to deal with the fact that the stories are fragmented and in no way interconnected, what need is there for the constant creation of banal thematic and graphic (and, to a lesser extent, symbolic) parallels? At least the similarity of the stories shouldn’t be so obvious and constantly emphasised through the off-screen commentary by one of the many narrators. Insufficient use of the fact that most of the stories are told by someone, in the form of a diary, a letter or a book, from the position of an interrogated prisoner or a respectable elder, represents another promise that the film makes and yet fails to develop (we only hear the narrators’ voices; otherwise, they remain unseen and do not actively get involved in the narrative, nor are they ever interrupted as it unfolds). Whatever the artistic intention may have been, which is not made very clear at all by the commercial rendering of the whole project, Cloud Atlas seemed to me like constantly interrupted intercourse without a proper climax. In exchange for the attention that I invested, and which had nothing to fixate on in places, I expected a more valuable reward than a message along the lines of “we have to help each other”, which I found to be ridiculous coming from a film that wants to break down conventions. 70%

Fifti-fifti (2011)

“I’m Adam Lerner, schwannoma neurofibrosarcoma.“ Another developmental stage of the bromance genre. Apatow’s comedy is intertwined with a “dying” melodrama. The boy-girl romantic storyline serves mainly as means of presenting the protagonist in greater detail, but it doesn’t answer the question of whether Adam’s girlfriends leave him melodrama because they’re bitches (as Kyle clearly believes) or because of his bland character and lack of will to change anything. Conversely, most of the truly touching moments are provided by the bromance storyline that sensibly uses Rogen’s committed (only?) position that he is a horny idiot and doesn’t care. He credibly complements Gordon-Levitt’s decent “I don't drink, I don’t smoke, I don't have a driver’s license” character (whose only bad habit is apparently biting his fingernails). The striking contrast between the two central characters is entertaining and their friendship is believable, while also offering two possible concepts of the human body – for survival/for satisfaction through pleasure. The laid-back pace of the narrative, sensitive incorporation of a serious subject into a comedy and the reduction of sentiment are definitely not qualities seen in every cinematic enrichment of oncological discourse. 50/50 not only enriches that, but also expands on it by putting a spotlight on false compassion and selfish unwillingness to take the negative with the positive, which is achieved through an initially likable girlfriend. Adam’s subsequent depressing loneliness casts doubt on the validity of the saying “live with people, die alone”. Some people are assholes, dying alone is a drag and living with a tumour involves pain, fatigue and vomiting. Banal, but true. The conveying of the knowledge that there may be no "after" was among the most powerful instance of such a message that I have ever experienced thanks to a film. Vastly superior to carcinogenic dramas. 85%

Egy hely a nap alatt (1951)

A melodrama with very dark undertones and one of the best presented instances of frustration. Despite his deadly effort, George is unable to find fulfilment in his personal or professional life, and the American Dream, whose fulfilment he considers to be his obligation as an ambitious young man, turns into a series of stressful life choices, none of which turn out to be right. Or does he really love Angela as such and not just the unattainable lifestyle that she, as a woman from a higher social class, personifies in his eyes? The unanswered questions enable the protagonist to be perceived simultaneously as a culprit and as a victim of a society whose demands he wanted to satisfy at any cost. The melodramatic and noir levels are firmly intertwined. The film doesn’t switch to another genre at any particular moment; it only starts to accentuate it more. The composition of the shots, with space intentionally left empty and with appropriately placed objects, has a certain narrative value in and of itself, as it draws attention to the mental state of the characters and hints at what undertones will happen (the courtroom in the background before the fateful journey to the lake). The directing exhibits absolute control over every scene, thanks to which George Stevens was able to weave a more subversive message into the film through the mise-en-scéne than that which the script conveys (thus adding hints of other thwarted erotic desires to the Oedipal fixation on the mother). In addition to that, the film also offers an absolutely professional presentation of method acting and an emotional whirlwind that won’t let you catch your breath. 85%

Száguldó bomba (2010)

A train weighing a million tonnes, 800 metres long and packed with highly explosive material. And there is no one in control of it. Tony Scott goes big with Unstoppable. However, in a ranking of the most original action films, this wouldn’t place even in the top one hundred. The plot is blatantly p r e d i c t a b l e, which is somewhat justified only by the fact that it was inspired by actual events. The lives of children, animals and heroic government employees are in danger. Unstoppable doesn’t differ from Scott’s previous train ride (The Taking of Pelham 123) in the nature of the main character (a sensible ordinary guy who becomes a hero), the relative lack of psychedelic visuals for a Scott film, the large amount of pathos or the forced emphasis on family values, but only in the absence of a villain. A simple failure of the human factor is what triggers the action. This time, the idiots aren’t cops (though there is a delightfully unnecessary airborne pirouette performed by a police car); the bad decision is made by a boss, whose bourgeois ass ultimately gets kicked to the curb by the working-class hero’s actions. Unstoppable really comes across as an ode to people who work with their hands and feet, but the constantly fast pace won’t give you time to think about that interpretation. The camera is constantly in motion, shots are very short even during the brief dialogue scenes, and we have to divide our attention between multiple events happening in parallel throughout the film. Scott took the main limitation of trains, i.e. the ability to go only forward and backward, and turned it into the main strength of the action scenes (the whole film is essentially one long action scene). The last-second miss was just as breathtaking as the last time in silent slapstick, of which it’s impossible not to recall at least The General. Whereas Keaton worked primarily with the breadth of a shot, Scott rather uses its depth, as if he’s heading toward using a stereoscopic format. That would have been a treat. Unfortunately, it will never happen. The unstoppable Tony Scott has reached his final station. 75%

Nevelj hollót (1976)

Cría cuervos y te sacarán los ojos. Raise ravens and they’ll gouge your eyes out. Slow, sad, painful and difficult for viewers to grasp, this awakening from Francoism is the peak work of Saura’s metaphorical period. And the film is so packed with metaphors that it is perhaps impossible to watch it except through them. This situation is not made any easier by the narrative point of view, whose strong subjectivisation we are only incidentally made aware of. During the film, Anna repeatedly transitions from the position of the one who tells the story to the role of the person about whom the story is told, which raises the question of whether the current reference point is the future or the present. In any case, the young protagonist finds no consolation either here or there. Set in an old house, the narrative is clearly laid out in spatial terms. The girls leave that old house at the end, when they join the ranks of other seemingly innocent little creatures lost between a repressed past and an uncertain future. Though the plot plays out in the middle of the political and social centre of Spain, specific references to the reality of the time behind the high walls of the house break through only exceptionally. On the inside, everything external is transformed into representative symbols, into multivalent fetishes (which is best elucidated by the taking out of the parents’ belongings). A determinative aspect comprises the transformations in the relationships between the characters, as the power games playing out between them threaten to escalate into games of life and death. Whoever sets the rules, it is safely – and fittingly for the period after the real and symbolic death of the father – not men. The multiplicity of layers of meaning, which present themselves to us only with repeated viewings, makes Cría cuervos a satisfying film in analytical terms, though unfortunately at the expense of viewer satisfaction. 75%

A nap szépe (1967)

With their second collaboration, Buñuel and Carrière set out to explore a still relatively uncharted territory. Their case study on the issue of female masochism stands out thanks to the seriousness with which they approach the subject and the degree of understanding expressed for the protagonist. The depiction of Séverine, an outwardly respectable and loving wife who in reality is a woman longing to liberate her sexuality through more than just fantasies, fits in with Buñuel’s other portraits of bourgeois hypocrisy, but it is not caustic. The lack of imagination as the main sign of bourgeois stagnation does not apply to the protagonist – she can dream and thus untie herself from the role for which she was destined. The irony lies only in the fact that she desires the same thing in both her marriage and in her sex life, namely submissiveness. In all of her daydreams, she is the one who is bound, not the one who binds (i.e. she’s not a dominatrix). For her, the key to liberation is the essentially surrealistic crossing of the boundary between the imaginary world and the real world. These two worlds necessarily have to blend together in the partially dreamlike ending. Despite the extraordinary seriousness of the approach, (Jacques Lacan himself reportedly showed Belle de Jour as explicative material in his lectures), the film doesn’t suffer from academic rigidity. Buñuel remains faithful to his economical style, with fetishistic shots of legs, well-chosen colours and well-placed objects. And, of course, with a bit of mischief aimed at viewers (we are not told what is in the black box, but we are made aware of our own voyeurism through Séverine). This bold film about what women truly desire is still impressive today as more than just a demonstration of the young Catherine Deneuve’s beauty and the peak work of Yves Saint Laurent. 85%

Love Story (1970)

“Really, it doesn’t hurt.” It is remarkable and, given the subsiding unrest of the 1960s, understandable how American viewers showed enormous interest in conservative melodrama in 1970. Love Story represents a very cautious return to certainties. The pairing of perfect opposites points to the possibility of overcoming class differences and the subsequent restoration of equilibrium. In the 1970s, the already somewhat archaic class difference served the filmmakers as a surrogate for the more pressing social conflicts of the time – between various ethnic groups and between supporters of different political ideologies. Furthermore, a beautiful poor girl can be more easily passed off as a flawless ideal. As a fragile creature, Jenny lends herself to being protected, to benefitting from a feeling of financial and other forms of stability, which Oliver can offer her. In return, she gets him away from “animalistic” entertainment (hockey is shown as a rather aggressive sport) and more among people. By creating a harmonious family environment that he cannot find at home, she provides Oliver with the conditions he needs for undisturbed study. Jenny abandons self-improvement (after all, she’s already perfect) and gives priority to her vision of family life over her career. In her case, emotions triumph over ambition, which Oliver still hasn’t confronted. As in every Oedipal drama, here the problematic character is the father, who, as an old pragmatist, forces his son to prioritise a better social standing over a love that offers no gain. Despite the anticipated twist in the final third, Love Story is an admirably painless film, soft, gentle and fragrant like freshly laundered clothes from a television commercial. Without any truly bad characters or negative emotions, it is a symptom of the desire for something pure and unspoiled, for an impossible return to an earlier time (the film also addresses this irreversibility). The real tragedy of Hiller’s Love Story consists not in the film itself, since it lacks any depth, but in what it represents. 60%

Madame de... (1953)

Grand, overwhelming, bombastic in its melodramatic nature beyond the rather high emotional ceiling of the genre. The dubious fatefulness is not hidden behind the characters’ actions, but rises to the surface, and its involvement in the game is conspicuously pointed out to us several times (the bet on thirteen, the interpretation of the cards). The men here are active and observant; the women are passive, observed, constantly swooning, dealing with emotions and taking care of their outward appearance. They so conscientiously take care of their appearance that it seems natural when Louise treats her diamond earrings more tenderly than she treats the men who come into her life and who are consequently just unreliable, less glittering derivatives of those earrings. Music plays almost continuously, stirring emotions and inspiring the characters to dance. The dancers (of whom the grand prize for endurance goes to Christian Matras behind the camera) exhibit the same tirelessness, to the point that in one scene there is nothing left for an annoyed musician to do but to demonstratively pack up his things and leave. He is overwhelmed by the melodramatic determination of the film, which is only just getting into the final third, which is perhaps less active in terms of movement, but is unabashedly self-reflexive in its sense of irony. Ophüls’s peak work and the most action-oriented of the films in which the only real “surface” action takes place off-screen. 85%

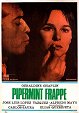

Peppermint frappé (1967)

If you’re interested in how Vertigo would look if it had been directed by Luis Buñuel according to Carlos Saura… 75%