Recenziók (838)

Párbeszéd (1955)

Varda had practically no experience with films or filmmaking prior to shooting her debut. The geometrically composed shots from unusual angles are inspired by the work of photographers such as Eugène Atget and Henri Cartier-Bresson (Varda herself began as a photographer) and the non-traditional structure, alternating (neo-realistic) anthropological scenes from the life of a fishing village (with non-actors) with lyrical scenes of dialogue by a pair of lovers (with actors) are based on Faulkner’s The Wild Palms. Interrupting the testimony on the difficult economic situation of fishermen and their families with the banal love story of a couple who seem uninterested in the outside world is intentionally frustrating and leads us to contemplate the relativity of the problems that seem significant to us in our lives. As in most of Varda’s subsequent works, the film’s dominant feature is contradiction, in this case particularly the contradiction between the social and the personal, documentary and performed. ___ The editor of the original, and in some ways slightly naïve and awkward, film was Alain Resnais, who introduced Varda to the cinephiles from the Cahiers du Cinéma clique and recommended that she start visiting the Cinémathèque in Paris. Though she did not know Visconti or any of the other directors whose influence contemporary reviewers perceived in her debut, she in fact surpassed the New Wave when she was the first to circumvent the system (it was common in France at that time to advance to the position of director through many years of serving as an assistant) and made a feature film very cheaply according to her own ideas, while rejecting the convention of formally staid and, in terms of reality, distant “dad cinema”. 70%

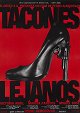

Tacones lejanos (1991)

High Heels is a film on the verge of a nervous breakdown. It is never far from slipping into Almodóvar’s self-parody, for which the very act of recycling previous motifs is more important than storytelling. If not for the strong central theme, which comprises the contradictory relationship between a mother and daughter who are seeking a way back to each other after many years of estrangement (just as young Spaniards tried to understand their homeland after Franco’s death), there would be nothing to hold the film together. It is too obvious that the plot was developed by cutting and pasting together the themes of famous “women’s” films (Stella Dallas, Mildred Pierce, All About Eve). The attempt to pay tribute to as many of the old masters as possible leads to the fact that, approximately every twenty minutes, there is a surprising plot twist and a slight change of genre (including a short musical interlude), none of which is quite “pure” (the grotesque police investigation). Though the film does not give us a chance to get bored, its rapid changing of moods makes it impossible to ever go more in depth and properly introduce the heroines. The constant referring to the fabricated nature of the narrative is not – as in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! and Broken Embraces – justified by the environment in which the story takes place (at most by the fact that at least two characters make a living by acting) and hinder any feeling of compassion for the protagonists, who, with the exception of a few authentic-seeming scenes (the dialogue in the church), serve only as lifeless structural elements. Despite its counterproductive anti-illusiveness (a phrase associated with killing, I admit), I liked how Almodóvar is continuing with his queer crusade against genre clichés. There are unreadable men who may have many faces, but still they desire the same thing and, in shots with a strictly symmetrical composition, divide (women) instead of connecting. In line with the distinctive artistic stylisation, the elegantly dressed ladies do not fulfil the role of mere decorative objects, but instead confidently use their fragile appearance (starting with a flashback from childhood, which was probably supposed to be a reference to Cria Cuervos). The father figure was excluded from the conventional family model and the women’s happiness does not depend on their relationships with men (the erotic scene between Rebeka with the man who had portrayed her mother only moments before could also be interpreted at the female level). In the end, the plot paradoxically serves to break down other, gender constructs. As ambivalent as this fact is, that is my attitude to High Heels as a whole, a postmodern film for better or worse. 75%

Barry - ronny/lily (2019) (epizód)

Forget about GoT; Barry offers the best fight scene. Furthermore, it takes place in broad daylight, so you can properly enjoy its choreography. In a surreal variation on Kill Bill, this series pushes the boundaries (of how far the protagonist can go without us completely condemning him) and goes far beyond the familiar space (similar to Donald Glover in some episodes of Atlanta) and even outside of the main storyline (no Sally, no Cousineau). In essence, however, it is another example of what Barry’s creators do best – defying the viewer’s expectations, repeatedly forcing you to ask “WTF?”. One might expect that the raw opening brawl, filmed in long layered shots with observationally impartial camerawork (while the participants occasionally disappear from the frame, which is typical of a series that maintains a dispassionate distance from its characters), would merely be a prologue to the story that follows. Instead of that, however, more and more complications accumulate in bizarre ways, and the whole thing is incredibly funny, exciting and grim (the flashback from the desert and the variation thereof at the end). This episode is the highlight of the season so far.

Csillogó álmom (2017)

Unicorn Store is a series of tonally diverse scenes that have no solid core and negate each other. Although it is (another) film thematising the necessity of giving space to one’s childlike imagination, it is shot without a hint of imagination (for a comparison, see basically anything by Michel Gondry). The only change compared to a dozen other filmic celebrations of infantilism and people suffering from the Petr Pan complex consists in the fact that the main protagonist is not a man (although it easily could have been; the female protagonist’s femininity plays only a marginal role). As great as my weakness for Brie Larson is, Samantha McIntyre’s layered screenplay would need much more sure-handed directing to keep it from tragically falling apart. 30%

Dumbó (2019)

The main protagonist of the animated Dumbo was an elephant. In Tim Burton’s live-action version, the baby elephant is primarily an attraction in a clichéd story of several nondescript characters who are paradoxically bothered by the fact that someone uses animals as attractions. Otherwise, it is a completely routinely directed film without spark and (surprisingly) also without memorable visual ideas and (almost) without humour. The original Disney film is an hour shorter, much more enchanting and touching, and contains a scene with pink elephants (to which Burton only briefly refers), apparently written under the influence of absinthe. In other words, it would just be better if you put on Dumbo from 1941 for yourself and your children. 50%

Túltolva (2019)

Lighter and funnier than Spring Breakers, The Beach Bum is a totally free and liberating film in which nothing much happens (to anyone) and practically the only “plot” development, in the final third of the film, consists in the always absent-minded Matthew McConaughey starting to wear women’s clothing and barking (which comes across as entirely normal, given the temperament of most of the characters and large number of bizarre situations). The Beach Bum is the perfect mental enema and the only Febiofest film after which I felt truly relaxed. 85%

Ha a Beale utca mesélni tudna (2018)

I understand that for viewers requiring a strong and original story, director Barry Jenkins’ serenade may be a disappointment (if the actual reason is not a combination of low emotional intelligence, latent racism and unwillingness to meet the work halfway, learn something about it in advance and try to understand its means of expression). The best melodramas, with whose conventions the film works inventively, always told primarily through music and colours (following the example of Claire Denis, Jenkins adds human faces and bodies, touches and glances, the way people communicate with each other verbally and nonverbally), were literal, very naive and narrowly focused their attention, at least outwardly, on expressing feelings within a relationship. If Beale Street Could Talk is not about overcoming conflicts and dramatic reversals. It allows us to experience (feel, perceive and touch) various situations in non-chronological order. With its composition with a regular rhythm, cyclical recurrences and overlapping scenes, it is reminiscent of a blues song or a lyrical poem. The aim is not realism, but an almost tangible evocation of a particular moment, mood and emotions, which are frequently contradictory (love, pain, sadness, laughter). However, politics also come into the film through the feelings – because we want (to see) a satisfying love story, together with the young couple we experience helplessness and disappointment from a world that repeatedly betrays them, which appeals to them only in order to remind them that because of their different skin colour, they do not have the same right as others to be blithely in love. If Beale Street Could Talk is a spellbinding film of extraordinary fragility, rare in the context of today’s film production due, among other things, to the above-standard requirements placed on the audience’s perceptiveness (which is in part because its tactile character arouses even those senses whose existence you are not aware of when watching other films). 90%

Angelo (2018)

Angelo is a film that only sporadically allows us get close to the characters. At the same time, it never receives their gaze, as it follows them with neutral shots throughout its runtime. This is most apparent during dialogues, which basically are not handled by means of standard cuts from one speaker to the other. We look in only one direction. Instead of being drawn into the picture by the shots/counter-shots, we remain in the position of impartial observers. This observational style, with which Schleinzer previously worked in Michael, underscores the central theme of human objectification. Angelo is exhibited at first. He later begins to appear on his own, but he portrays a learned role that is not a reflection of his true identity, but rather of the distorted (stereotypical) ideas about African culture held by white people (who, through this “colonisation of the mind”, by subordinating foreign elements to their own ways of representation, assert their dominance – therefore, the protagonist’s gaining of independence is the worst sin that he can commit). Depersonalised static shots à la tableaux vivants (contemporary fine art also associates natural lighting and a well-considered choice of colours of the environment and costumes) make the film difficult to access, but, at the same time, the distinctively elliptical narrative with a large number of hints that retroactively give meaning to certain scenes, forces us to fully engage with it. From these two opposing movements that the film requires from the viewer, a special dynamic arises, due to which, together with subversive anachronisms in the mise-en-scène, strict division into chapters and very cynical pointing scenes, Angelo is not a boring film despite its slow pace, but rather a very stimulating work that entices the viewer to watch it again. 90%

Friedkin Uncut (2018)

I was quite irritated that the narrative has almost no order and constantly jumps between films and topics (and the shots of Friedkin’s appearances at various festivals are randomly inserted into it). The commentary of the crowd of celebrities contributes to the distraction and does not provide much that is beneficial. If the director had simply sat Friedkin down in a chair and let him talk for an hour and a half about his life and career (i.e. the model successfully applied to the documentary De Palma), we would have learned more. At the same time, the entertainment element and briskness of the narrative would not have had to suffer from this, as Friedkin is a pleasure to listen to for his impudence, (film) erudition and supply of humorous stories from filming (and he obviously likes to listen to himself, even if he is not too infatuated with himself to appreciate someone else’s talent – for example, the best American director today is, in his opinion, a woman, Kathryn Bigelow). I appreciate the fact that the film (mostly) does not unnecessarily repeat the information known from earlier documentaries about the shooting of The Exorcist or The French Connection, and attempts to reveal lesser-known facts. On the other hand, it is regrettable that it does not give more space to other, more obscure projects, not only the documentary The People vs. Paul Crump, which together with television training pushed Friedkin toward a veristic way of shooting and an emphasis on authenticity and immediacy at the expense of elegance (the first take is fine, even though the whole crew can inadvertently be seen in reflection in the shot, because “who gives a fuck”). ___ Of the many memorable quotes of a filmmaker who is likable for his casualness and the fact that he rarely bothered with what was appropriate (whether in public statements or narrative conventions), I would have at least this inscribed: “Nobody can top Buster Keaton.” 75%

Hale County This Morning, This Evening (2018)

Hale County This Morning, This Evening is probably the best antithesis of last year’s Green Book. A visually captivating search for alternative ways to represent black bodies, which is to say the African-American minority. With a very loose structure, an associative montage and musical rhythm. No conflicts, no drama, no white people. Nothing that you would expect from a movie with a racial subtext. Just life the way it is lived. As RaMell Ross explained after a screening, a white American audience found the film boring because nothing happens in it, because it was just a sequence of everyday scenes. African-Americans, on the other hand, appreciated the fact that someone viewed them primarily as people, not as members of a particular ethnic group defined by skin color and burdened with numerous stereotypes. It is good to be aware of the kind of thought patterns and expectations with which we approach the narratives of members of a given culture. With its concept (unlike Green Book, it does not reinforce myths, but rather dismantles them; it does not lead to anything specific, does not assert anything definitive, and does not judge anyone), Hale County provides an excellent starting point.