Recenziók (840)

A szél másik oldala (2018)

Jake Hannaford, a passionate hunter of Irish descent, as well as a chauvinist and racist, is not so much an alter ego of Welles as he is of John Huston. The Other Side of the Wind captures the last days of classic Hollywood, or rather the decline of the world represented by macho Huston-type patriarchs. Because of her indigenous origins, Hannaford sees the lead actress of his film as an exotic exhibit and mockingly calls her “Pocahontas”. The actress initially reacts with hateful looks and later vents her frustration by shooting at figurines. Hannaford’s publicist, based on film critic Pauline Kael (who couldn’t stand Welles), is not reluctant to engage in open verbal confrontation with the director when she repeatedly points out the macho posturing that he hides behind. The women defend themselves and the men are not happy about it. ___ By giving the female characters more space and enabling them to give expression to their sexuality, Welles comes to term not only with Hollywood, but also with his own legacy. Like late-period John Ford, whom Welles greatly admired, he critically reassesses the themes of his earlier films. At the same time, however, doubts arise as to whether the way in which Oja Kodar’s character is presented in Hannaford’s film (sexually aggressive, captivating an inexperienced male protagonist) also says something about Welles. ___ Hannaford's unfinished magnum opus is clearly a parody of the works of American filmmakers who during the New Hollywood era responded diligently to European works by shooting pretentious and incoherent would-be art films packed with eroticism and conspicuous symbolism. More or less naked, beautiful and young actors wordlessly wander around each other in dreamlike interiors and exteriors. It doesn’t seem to matter that the characters don’t follow the sequences of Hannaford’s film in the right order (if anyone actually has any idea what the order is supposed to be). As Welles divulged in an interview, he shot the film with a mask on, as if he wasn’t himself. Therefore, why should we associate with him what Hannaford’s work says about women and female sexuality? ___ The parodic imitative style, which was not peculiar to Welles, was due also to the raw, intentionally imperfect hand-held shots from a party, reminiscent of the then fashionable cinema-verité. Completed long after Welles’s death, the film is basically a combination of two styles that Welles would not have employed. The question of who Jake Hannaford was (like the question of who Charles Foster Kane was in Citizen Kane) is less relevant in this context than the question of who the creator is and who is imitating whom, which Welles quite urgently asks in the mockumentary F for Fake, which, with its fragmentary style, has the most in common with The Other Side of the Wind. ___ For example, Peter Bogdanovich, who was considered to be an imitator of Welles in the 1970s, plays Hannaford’s most diligent plagiarist in the film. The defining of his character through imitation of someone else, however, is done ad absurdum, when he occasionally begins to imitate James Cagney or John Wayne in interviews with journalists. Though Welles incorporates media images of influential figures into his film, he also ridicules them as improbable and untruthful. All of these contradictions could be part of an effort to offer, instead of the retelling of one person’s life story, an expression of doubtfulness about the ability to recognise who someone really is. ___ Though, thanks to Netflix, Welles’s film can theoretically be seen by far more viewers than would have been possible at the time of its creation, the manner of its presentation by the streaming company recalls a moment from Hannaford’s party, when the producer lays down reels of film and says to those interested in a screening, “Here it is if anybody wants to see it”. Netflix helped to finish the film and raised its cultural capital by presenting it at a prestigious festival, and then more or less abandoned it, as if cinephiles who love more demanding older films were not a sufficiently attractive audience segment. ___ With Welles’s involvement, the film, which was completed 48 years after it was started, would have perhaps been more coherent, had a more balanced rhythm and conveyed a less ambiguous message. At the same time, however, all of its imperfections draw our attention to its compilation-like nature, or rather the convoluted circumstances of its creation – we think about who is in charge of the work, who created it (perhaps Jake Hannaford, whose “Cut!” is heard after the closing credits) and what it says about him, which was probably Welles’s intention. The Other Side of the Wind is a good promise of a great film. 80%

Barátom, Róbert Gida (2018)

Even though Eeyore was my favourite nihilist before Bernard Black, I never became a member of the Winnie the Pooh fan club. Therefore, I was curious about Christopher Robin, a sort of sequel to the previous animated films, mainly because of the director and one of the screenwriters (mumblecore veteran Alex Ross Perry, whose influence is apparent especially in Eeyore’s heavy existential lines). ___ A total of five screenwriters alternated in and out of the project during its development, which may be the reason that the result seems so clumsy and disorderly, and that the film never gets a firm footing and does not work as family viewing, as Disney apparently intended. The story, which is about an overworked man focused on profit and performance who evidently suffers from PTSD due to the war and neglects his wife and daughter until he rediscovers his inner child thanks to a talking teddy bear (and a pig and tiger and donkey) or, rather, until he stops denying his existence and hiding the talking stuff animals from others, is mainly inconsistent. At times, it is basically a serious drama about an empty, bland existence, and at other times exaggerated slapstick (especially the scene with Gatiss, who is reminiscent of villainous capitalists from classic Hollywood movies). The style is predominantly very naturalistic, with desaturated colours, a hand-held camera lying alongside soldiers in the foxholes of World War II, and animated characters that look like actual soiled stuffed animals from the protagonist’s childhood. At still other times, however, its playfulness lends the film a touch of liberating magical realism á la Paddington (chasing Pooh around the station, the final pursuit). The rhythm of the narrative is similarly unbalanced, as it lacks momentum and a clear aim. The film is unable to decide whether Christopher’s priority should be his family life, his career or his relationship with Pooh, as if completely forgetting about one of these motifs for a moment and blindly following another instead of somehow cleverly combining all three. Some scenes take too long to get to the point (the fight with the Heffalump), while at other times a segment of the story explaining how a character gained certain information seems to be missing (for example, Madeline’s knowledge of the napping game). ___ The film is in large part too serious and sombre for children, and is even frightening during scenes from the fog-enshrouded Hundred Acre Wood (especially in combination with the red balloon, which is apparently intended as a reference to Albert Lamorisse’s film, but it’s impossible not to recall the psycho clown from It). For adults, the film is sloppy in dealing with the rules of the fictional world, unconvincing with the forced optimism of the conclusion and banal in its approach to psychology (the miraculous transformation of Robin’s thinking), relationships and corporate capitalism. ___ At a time when we need to more vigilantly watch where the current world is heading and act accordingly, the central idea that doing nothing and looking nostalgically to the past can improve our present and that our childhood misses us as much as we miss it is a bit off base (though fully in accordance with the constant churning-out of remakes of old films and the fetishisation of past decades, not to mention that the call to live in the present will certainly resonate strongly with today’s proponents of concepts such as mindfulness). Other films (such as Toy Story 3) have dealt with a similar idea more sensitively. But in the end, this idea was the main reason that Christopher Robin was made and more or less holds together. 60%

Bolti tolvajok (2018)

Koreeda further develops the theme of alternative family models that do not depend on blood relations, but rather on what is shared by those involved (he again works a lot with taste memory here) and whether they feel comfortable and safe together. At the same time, the film shows, but by no means excuses, the dubious foundations of some interpersonal ties. The members of the “family” are united not only by love, but also by financial dependency or a dark secret that is gradually revealed through well-thought-out dosing of information (there is thus a pseudo-detective storyline that keeps us in suspense until the end). Because the head says something different than the heart, there is no simple answer to the question of who should ideally stay with whom at the end of the film. Replacing exposition with the gradual revealing of the protagonists’ past and strengthening of the ties that unite them contributes to the variability of the relationships and forces us to constantly reassess our opinions of the individual characters, among whom Koreeda “democratically” divides attention. At the same time, we get an uncompromising cross-sectional sociological view of modern Japanese society, from teenagers who either prefer to go abroad or to receive money for “swinging their breasts” (and offering company to emotionally deprived young men), through the working class that has a form of certainty, to seniors killing time with gambling machines. At its core, Shoplifters is a rather simple drama that is dark but not completely hopeless, while also being complex in many respects. Like all of Koreeda's films, it is characterised by a slowly paced narrative (divided into several blocks divided by fade-outs), a jagged mise-en-scène and economical yet precise camerawork that involves no unnecessary movements and adapts its point of view to the individual characters according to the needs of the narrative. Though Shoplifters does not in any way manipulate you emotionally, it can, without applying any pressure, bring you to a point where all it takes is for one character to utter a single word and you will find yourself in tears. This is further proof of Koreeda’s unpretentious mastery of his craft. Though it is perhaps formally less inspiring than The Third Murder, more accessible to viewers than Nobody Knows and not as fragile as Still Walking, it is still one of the best-directed films I’ve seen this year. Twice so far, but I will definitely come back to it. 90%

Bosszúállók: Végtelen háború (2018)

Infinity War combines within itself several excellent (Thor’s main storyline) and a few average aspects of Marvel movies: achievement of the objective is delayed due to the fact that the protagonists repeat the same “mistake” again and again, by means of which the filmmakers incessantly and semi-pathetically tell us what the film’s central idea is, the most robust action happens basically just to cut something epic into the trailer when the directors switch to melodramatic mode (which they do much more frequently than before), some of the dialogue is pretty “cheesy”, the plot becomes more predictable over time, the postponement of the inevitable more tiresome and the narrative more monotonous ... It holds together thanks mainly to the emotionally dense revealing of negative motives, to which the turning points and the division of the narrative into three large plot segments are tied. ___ The movie strives for an uncompromising climax, but the story is not pervaded with a serious approach to nearly the same extent as in Logan’s or Nolan’s Batman films. Priority is still given to entertaining the viewers and not forcing them to think about the sense of violence or the cost of heroism/humanity. I still consider the best Marvel movie to be the second Captain America, whose stylistic purity and narrative compactness that the rather episodic Infinity War can only dream about, given how it leaves some of the characters out of the story for so long that you almost forget they are in the movie and alternates between too many styles (while quite logically not having its own distinctive style like Thor: Ragnarok or Black Panther). ___ This time, Feige and co., like Singer in the markedly more ponderous X-Men: Apocalypse, go to the limit of how many prominent characters can be crammed into a single feature film without it falling apart, while making sure that viewers who are unfamiliar with the previous eighteen films do not get completely lost and that viewers who are well acquainted with the MCU get what they want without their heads exploding. It’s hard for me to imagine where they can go next and it can b probably be considered a great success that the result is not much less consistent and that it generally has a balanced rhythm (due in large part to the rapid and humorous verbal exchanges). ___ Infinity War is not revolutionary and it contains nothing so stimulating (in terms of style, content or narrative) that I want to see it again anytime soon, but for all the money, it is unambiguously a superbly calculated blockbuster that cleverly serves the fans (starting with the entrances of the individual heroes on the scene), making its production circumstances reminiscent of the golden age of the large-scale Hollywood system (a regular stable of stars + an unchanging circle of collaborators). Furthermore, it can be unsettling for the more sensitive viewers who have become a bit attached to the Marvel superheroes over the years (I myself had a rather unpleasant feeling of helplessness and anxiety during the credits and for a moment afterwards). 80%

Csodálatos fiú (2018)

Beautiful Boy is a film that has nothing to say (a few informational titles at the end bear the sole message). It merely shows pain and attempts to be moving. The first half is at least remarkably well structured. The narrative does not move forward, but only – often by means of sound bridges – sinks into itself (like a person on drugs). For no apparent reason, the filmmakers abandon the fragmentary, highly subjective narration and alternating flashbacks of a father and his son, and the rest is conventional misery porn with a terrible selection of music and spasmodic actors (Chalamet is capable of great acting, but needs stronger directorial guidance; here, he seems to be a bad Robert De Niro imitator) who, instead of normal sentences, deliver lines like “I missed you more than the sun misses the moon” with a straight face. However, I admit that I felt like crying at the end. Because of the wasted two hours of my life that I will never get back. Perhaps I am being overly harsh, but I have a strong aversion to this kind of film, which uses someone’s actual misfortune for terribly cheap and self-serving exploitation. 20%

Csuklyások (2018)

Previously it would have been a biographical drama or a heist film, but to express his political viewpoint this time, Spike Lee uses and reworks for his own needs the conventions of cop films about dual identity. The obstacles that the heroes have to overcome in accomplishing their mission come not only from the outside, but also in the form of their colleagues and superiors, who are unable to let go of their own prejudices and represent a system that disadvantages a certain part of the population. The pairing of two disparate characters serves for more than just creating comical situations that bring levity to a serious topic. It is also a condition for the implementation of Stallworth’s bold plan and, at the same time, expression of the film’s central conviction that the path to success is conditioned by cooperation, the struggle for shared values (though each one is completely different, they appear before the KKK members as one person), which can also be understood as a disputation with blaxploitation films, whose style BlacKkKlansman imitates. ___ The two protagonists start to think more about their respective identities following confrontations with white nationalists, who see them, as a black and a Jew, as a threat comparable to the plague and cholera. For example, in reply to the question of whether he is a Jew, Zimmerman initially answers “I don't know”. He later admits that, because of assimilation, he had never thought about his Jewishness, but he is now beginning to reconsider his position. Like his partner, he stops taking his infiltration of the Ku Klux Klan as nothing more than a job, as it becomes a personal matter for him. While Stallworth stops running away from the fact that he is black, Flip begins to proudly defend his Jewishness “thanks” to a group of anti-Semitic imbeciles. ___ Racists legitimise their words and actions by creating artificial enemies and spreading fear of a race war or the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy. Their vocabulary plays a fundamental role in this, though it does not have any sort of richness and displays an elementary ignorance of grammar, but it is also expressive enough to elicit strong emotions and attract unthinking crowds. Emotions replace the ability to work with facts and to argue more thoughtfully. One of the bigots reveals the absence of elementary logic in his attitudes when Flip warns him that it is nonsensical to deny the Holocaust, during which several million Jews were murdered and was thus the most amazing event in history from a white Nazi’s perspective. Within the KKK, relationships are established exclusively on the basis of shared hatred. Joining the organisation is conditioned by knowledge of the hate code (various terms of abuse for anyone who is not a white heterosexual American). However, it is necessary to make the language of this closed group widely known, for example with the aid of Hollywood epics such as The Birth of a Nation. ___ The wave of racially motivated violence in the 1970s was a backlash to some of the minor victories achieved by African-Americans in the previous decade. Similarly, the strengthening position of the extreme right in America today, stoked by the statements of the sociopath whom Spike Lee calls the “Orange motherfucker” and “Agent Orange”, can be seen as “retaliation” for the eight years of the Barack Obama administration. Lee’s film is permeated by parallels with current events in the United States and Europe. Even without the shocking postscript, it would be clear that, as in his earlier films, Lee used a historical theme to draw attention to the persistent intolerance of certain social groups. Though the style changes, the essence remains and the world will continue to need many heroes like Ron Stallworth and Heather Heyer. BlacKkKlansman says as much, perhaps without much nuance, but urgently enough to open the eyes of at least a few people who do not yet have totally whitewashed brains. 90%

Csúszópálya (2018)

Director Bing Liu spent twelve years filming two of his friends from the skateboarding community as they grew up and attempted to come to grips with roles for which they were not prepared. For Zack, a life test comes in the form of the birth of his son. Keire, six years younger, is forced to take on a more responsible attitude following the death of his father. In parallel with the trajectories of their lives, we see the transformation of their relationship with the filmmaker, whose own family history has an impact on the shooting process. Despite the many intoxicating intermezzos in which the protagonists indulge in skateboarding, this bumpy ride is not a film about skateboarding, but primarily about the effort to overcome economic and social constraints and to enter adulthood as a self-confident and independent person who will not be limited by his class, family relationships or race. Minding the Gap is an intimate, intelligently constructed film that retains an element of lightness despite the gravity of the topics that it addresses. 90%

Deadpool 2 (2018)

Deadpool 2 is a touching family melodrama about the importance of traditional values, with a hero who wants to kill himself most of the time, vomiting acid and brutal action scenes accompanied by dubstep or Enya (decide for yourself which is worse). It is as comparably entertaining as the first one, though at the same time darker and more layered emotionally and in terms of storytelling. ___ Retrospectively (like a large part of the first instalment) only the first 20 minutes or so are narrated, after which film-noir turns into a buddy movie (from prison). Only the second half is a superhero team flick (Rob Delaney as Peter deserves a spin-off). The protagonist’s objective and the role of the villain (again played by the excellent Josh “Thanos” Brolin), who arrives on the scene relatively late, unexpectedly change several times. Everything is connected by the melodramatic background with the late/impossible reunion and (re)construction of the family. This primarily involves the main protagonist’s inner conflict, not the destruction of the world as in other comic-book movies. Therefore, I was not bothered by the numerous entirely serious scenes without self-deprecating humour (besides, if you have one of the characters refer to the screenwriter as an imbecile after some bad dialogue, nothing about that bad dialogue changes). Thanks to those scenes, you take the characters more seriously than they take themselves and the conclusion stimulates the right emotions (in this respect, Deadpool is more self-sufficient than Infinity War – in order for you to be moved, you do not have to know the preceding 18 films; you only have to know what you have seen over the past two hours). ___ The best bits are the opening credits parodying Bond movies, the post-credit scenes (or rather mid-credit scenes, as nothing remains after the closing credits) and jokes that truthfully call out the shortcomings of comic-book films that lack good humour, something with which Deadpool abounds. Besides the competition from DC, this is again captured mainly by X-Men, referred to as an outdated, gender-incorrect metaphor of racism from the 1960s. Conversely, it freezes routine action scenes with confusing editing (with the exception of a few more fluid moments, which with their choreography bring John Wick to mind), which, as in the case of most major productions of this type, was probably not under the control of the director himself, but of the second unit (and subsequently the people in charge of CGI). ___ Despite that, Deadpool 2 is very good summer entertainment whose creators managed to come up with enough ways to surprise us both with content and with the construction of the story and by using the conventions of various genres even without the possibility of somehow repeating the “wow effect” of the first film from beginning to end. 80%

Diane (2018)

In his belated feature-film directorial debut, former film critic and documentary filmmaker Kent Jones offers a sensitive character study of a working woman from a small city who forgets to take care of herself as you she takes care of others. With every scene, this long-resonating, stylistically unobtrusive film is remarkably rich in meaning. Diane relies on a highly subjective narrative, the director’s sense of detail and the deeply felt acting of Mary Kay Place, which strengthens our affinity for the main protagonist while contributing to doubtfulness with respect to her mental health. The film is also valuable due to the matter-of-factness with which it states that at the end of our life story, no major point will be revealed, but only death in loneliness. 80%

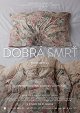

Dobrá smrť (2018)

The Good Death is a documentary portrait of an English woman who intends to undergo euthanasia. Seventy-two-year-old Janet does not want to wait until her unfortunate health condition, caused by hereditary muscular dystrophy, deteriorates to such an extent that she becomes completely legally incompetent. She would lose the ability to make her own decisions supported by clear, rational arguments. She is not afraid of death. She has accepted it just as she previously accepted her illness and the fact that life is not fair and that it is necessary to deal with it in accordance with her current options (unfortunately, the film does not elaborate on the fact that not everyone in her situation has the same options and a "good" death is a kind of privilege, but I understand that such an exploration would be a detour from the direction in which the film’s attention is focused). While Janet determinedly and resignedly approaches the day when the pentobarbital solution will end her suffering, we follow in parallel the story of her son, who suffers from the same disease and anticipates the same fate.___Despite the apparent similarities in the way both social actors are filmed, however, her son’s storyline is more hopeful, as Simon is involved in research that could lead to the discovery of treatments for the currently incurable disease. The impressive visual concept, the use of contrasts and parallels, the heroine’s poetic off-screen commentary and the unforced mise-en-scène to illuminate Janet’s previous life keep the film in the space between procedural drama and open-minded consideration of how death is “natural” (two religious commentaries on euthanasia were typically included in the film – according to one, God should decide on our existence and non-existence; according to the other, God does not want us to suffer and it is therefore acceptable if we decide to end our own lives). Despite the occasional intensification of the melodramatic level through the use of mournful music and the aestheticisation of actions connected with one’s final affairs, the film does not resort to the exploitation of human misery. It is shot with great humility and understanding both for those who have decided to leave and for those who remain. 70%